"Why this ad?" (WTA) functionality has suddenly become hot news in the pharmaceutical industry. For those of you who have not noticed it previously, or heard the hubbub, here's the deal.

Google takes transparency quite seriously, and given the privacy concerns everyone has about trusting any company with as much information as Google maintains on people, it's understandable why.

As part of its transparency efforts, Google added some new functionality to its search engine marketing (SEM) results a few years ago. Users are able to learn why a particular ad is being presented to them.

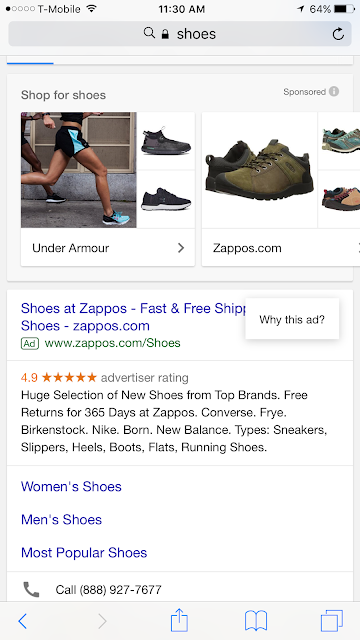

In practice what users see is a symbol (either an encircled letter "i" or a green triangle) next to a promoted message.

|

| The red box surrounds the symbol in mobile and desktop search results that enable the user to learn more about the ad targeting. |

|

| These images show the "Why this ad?" popup that users see after clicking on the symbol. |

Clicking on the question prompts a further box to appear with information about why that particular ad was displayed to the user.

There are differences between the functionality in a desktop/laptop and a mobile environment. For example, in the mobile environment, the shadow box effect obscures and separates the underlying ad from the information supplied by Google more than the overlaid box alone that is seen on a laptop.

Both mobile and desktop ads display the root URL of the destination from the ad at the top of the box, and both allow signed-in users to opt out of seeing ads from that URL via a slider at the bottom of the box, which again displays that root URL of the destination webpage.

The reasons provided for what the ad is based on will vary depending on what caused the ad to appear. The factors listed in SEM ads will always include the search terms and might also include factors such as location (if the user permits Google to access that information) or that the user has previously visited the site.

The WTA information and functionality is not advertising content. No advertiser is permitted to alter this content or has any control over it. Advertisers indirectly influence it via the parameters that they set for determining when their ads appear. For example, if an advertiser targets only users who have previously visited their website, then that factor might appear, whereas if the targeting is solely based on the search terms, then it would be less likely to appear.

Some people have recently learned about this functionality and raised questions about whether it poses a potential risk for violating the Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) advertising regulations.

The scenario these people envision is that a company is using a redirecting ad, which by definition doesn't include the brand name in the ad itself but instead redirects users to a Brand.com website. If a user sees such an ad and clicks on the WTA symbol, and then clicks a second time on the "Why this ad?" popup, the user will see the brand name appearing because the brand name is most often the root URL of the home page for the destination of the redirecting ad.

The FDA has made clear via previous enforcement actions (such as many of the infamous 14 search letters from 2009) that merely using the brand name in a URL is considered by the FDA to be a mention of the drug for the purposes of advertising the product, and carries with it all of the requirements associated with any other product name mention.

Depending on the type of ad, the requirements might include only the inclusion of the brand and generic names and the relative sizing of the two, or they could be as extensive as the inclusion of the complete indication statement, dosage form, etc., associated with a full product promotion.

Let's first address the idea that a company could be out of compliance because the brand name of its product appeared without the generic name. The brand name is appearing in a location over which the company has no control. As mentioned earlier, the popup box is not itself an advertising unit. Companies cannot ask Google to change the information that appears in the box, and they have no control over it. There is some indirect influence, but this is definitely not a company-owned or company-controlled communication. Consequently, it would seem that this appearance of the brand name would be analogous to a newspaper using the brand name, and newspapers frequently use the brand name of drugs without including the generic name.

FDA would never take enforcement action against a company for that type of third-party action, and it is hard to imagine that they would do so here.

Then there's a second issue. Depending on whether a user is accessing the ad via a mobile device or a desktop computer, the user might be able to see the underlying ad at the same time as the overlay. It is certainly possible that this could mean that a user sees both the brand name and some of the underlying redirecting ad, which was so carefully designed by the company to avoid including the brand name. In some cases, there is information in the redirecting ad that would be considered by the FDA to describe the product's use. And in that same set of infamous letters from 2009, FDA made very clear that including some description of a product's use with the brand name carries with it the full requirements associated with a complete production promotion (indication statement, etc.).

Does that pose a risk of FDA enforcement?

For FDA to take an enforcement action in this instance, FDA would have to hold a company accountable for a message over which it has complete control (the underlying redirecting ad) when that message is combined with a separate message over which the company has no control.

It seems hard to believe the FDA would do something like that.

I admit that I would be happier if the WTA overlay box behaved the same way on a desktop as it does on a mobile device, with the shadow box effect that obscures the underlying ad and that also makes the separation between the two communications more clear.

But even without this change being implemented, I see an extremely low risk that FDA would take an enforcement action for an advertising publisher creating a tool that reveals more information than an advertiser wanted included in their ad.

While Google is determining what (if any) changes to make to its WTA functionality in light of the latest stir, I would submit for all of the reasons above that this poses a low risk of enforcement.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.