Last week, the FDA published a final version of the Product Name Placement, Size, and Prominence in Promotional Labeling and Advertisements.

FDA has been remarkably active on this topic, as this is now the third update to the guidance in the past five years. People who have been following this guidance will be pleased to hear that there's little new. Though there are many changes, there are no substantial changes from the 2013 version. The most significant development in the new guidance is the provision of examples demonstrating FDA's principles about prominence of the product name.

If you'd like a quick overview of the guidance, I suggest this one from Intouch Solutions.

WTA?

Disclosure: I sit on the Google Health Advisory Board, and Google has been a client of PhillyCooke Consulting. Nothing in this post has been shown to Google or received the endorsement or approval of anyone at Google. I have discussed the topic of this post with Google employees.

"Why this ad?" (WTA) functionality has suddenly become hot news in the pharmaceutical industry. For those of you who have not noticed it previously, or heard the hubbub, here's the deal.

Google takes transparency quite seriously, and given the privacy concerns everyone has about trusting any company with as much information as Google maintains on people, it's understandable why.

As part of its transparency efforts, Google added some new functionality to its search engine marketing (SEM) results a few years ago. Users are able to learn why a particular ad is being presented to them.

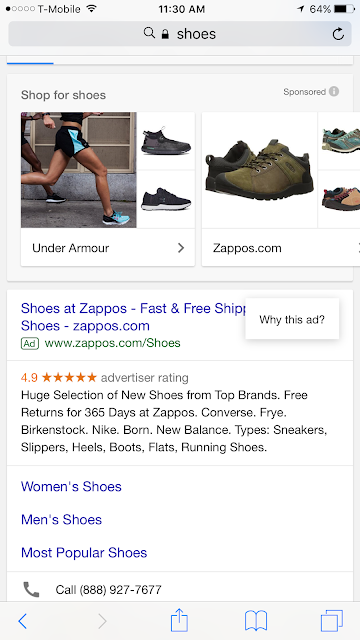

In practice what users see is a symbol (either an encircled letter "i" or a green triangle) next to a promoted message.

Users who click on the symbol see a question appear, "Why this ad?"

"Why this ad?" (WTA) functionality has suddenly become hot news in the pharmaceutical industry. For those of you who have not noticed it previously, or heard the hubbub, here's the deal.

Google takes transparency quite seriously, and given the privacy concerns everyone has about trusting any company with as much information as Google maintains on people, it's understandable why.

As part of its transparency efforts, Google added some new functionality to its search engine marketing (SEM) results a few years ago. Users are able to learn why a particular ad is being presented to them.

In practice what users see is a symbol (either an encircled letter "i" or a green triangle) next to a promoted message.

|

| The red box surrounds the symbol in mobile and desktop search results that enable the user to learn more about the ad targeting. |

|

| These images show the "Why this ad?" popup that users see after clicking on the symbol. |

Clicking on the question prompts a further box to appear with information about why that particular ad was displayed to the user.

There are differences between the functionality in a desktop/laptop and a mobile environment. For example, in the mobile environment, the shadow box effect obscures and separates the underlying ad from the information supplied by Google more than the overlaid box alone that is seen on a laptop.

Both mobile and desktop ads display the root URL of the destination from the ad at the top of the box, and both allow signed-in users to opt out of seeing ads from that URL via a slider at the bottom of the box, which again displays that root URL of the destination webpage.

The reasons provided for what the ad is based on will vary depending on what caused the ad to appear. The factors listed in SEM ads will always include the search terms and might also include factors such as location (if the user permits Google to access that information) or that the user has previously visited the site.

The WTA information and functionality is not advertising content. No advertiser is permitted to alter this content or has any control over it. Advertisers indirectly influence it via the parameters that they set for determining when their ads appear. For example, if an advertiser targets only users who have previously visited their website, then that factor might appear, whereas if the targeting is solely based on the search terms, then it would be less likely to appear.

Some people have recently learned about this functionality and raised questions about whether it poses a potential risk for violating the Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) advertising regulations.

The scenario these people envision is that a company is using a redirecting ad, which by definition doesn't include the brand name in the ad itself but instead redirects users to a Brand.com website. If a user sees such an ad and clicks on the WTA symbol, and then clicks a second time on the "Why this ad?" popup, the user will see the brand name appearing because the brand name is most often the root URL of the home page for the destination of the redirecting ad.

The FDA has made clear via previous enforcement actions (such as many of the infamous 14 search letters from 2009) that merely using the brand name in a URL is considered by the FDA to be a mention of the drug for the purposes of advertising the product, and carries with it all of the requirements associated with any other product name mention.

Depending on the type of ad, the requirements might include only the inclusion of the brand and generic names and the relative sizing of the two, or they could be as extensive as the inclusion of the complete indication statement, dosage form, etc., associated with a full product promotion.

Let's first address the idea that a company could be out of compliance because the brand name of its product appeared without the generic name. The brand name is appearing in a location over which the company has no control. As mentioned earlier, the popup box is not itself an advertising unit. Companies cannot ask Google to change the information that appears in the box, and they have no control over it. There is some indirect influence, but this is definitely not a company-owned or company-controlled communication. Consequently, it would seem that this appearance of the brand name would be analogous to a newspaper using the brand name, and newspapers frequently use the brand name of drugs without including the generic name.

FDA would never take enforcement action against a company for that type of third-party action, and it is hard to imagine that they would do so here.

Then there's a second issue. Depending on whether a user is accessing the ad via a mobile device or a desktop computer, the user might be able to see the underlying ad at the same time as the overlay. It is certainly possible that this could mean that a user sees both the brand name and some of the underlying redirecting ad, which was so carefully designed by the company to avoid including the brand name. In some cases, there is information in the redirecting ad that would be considered by the FDA to describe the product's use. And in that same set of infamous letters from 2009, FDA made very clear that including some description of a product's use with the brand name carries with it the full requirements associated with a complete production promotion (indication statement, etc.).

Does that pose a risk of FDA enforcement?

For FDA to take an enforcement action in this instance, FDA would have to hold a company accountable for a message over which it has complete control (the underlying redirecting ad) when that message is combined with a separate message over which the company has no control.

It seems hard to believe the FDA would do something like that.

I admit that I would be happier if the WTA overlay box behaved the same way on a desktop as it does on a mobile device, with the shadow box effect that obscures the underlying ad and that also makes the separation between the two communications more clear.

But even without this change being implemented, I see an extremely low risk that FDA would take an enforcement action for an advertising publisher creating a tool that reveals more information than an advertiser wanted included in their ad.

While Google is determining what (if any) changes to make to its WTA functionality in light of the latest stir, I would submit for all of the reasons above that this poses a low risk of enforcement.

FDA's One-click Study

At the beginning of November, FDA announced its intention to conduct a study looking at the so-called "one-click rule." As readers of this blog know, I've termed this, "The 'Rule' That Isn't."

The basic idea behind any version of the one-click rule is that companies can meet their fair balance requirement (21 CFR 202.1(e)(5)(ii)) by including a hyperlink to the risk information, rather than by providing the risk information itself in the original communication. As I've written about previously, this idea has had significant allure for marketers of prescription products but there has never been any indication from the FDA that it was open to it...until now.

I have been working with a few different clients preparing comments on the study proposal outlined by the FDA. Those will be posted to the docket and available for public view at a later date.

In this post, I wanted to take a step back and look at what this study means (and what it doesn't mean) for the immediate and future use of space-limited contexts by prescription product manufacturers and FDA guidance about this issue.

In 1998, FDA took its first enforcement action for Internet marketing. At the time, the FDA noted that "the link to the full prescribing information alone is insufficient to meet the requirements...that advertisements contain fair balance."

This began an 18-year history of the FDA making clear that it did not acknowledge a one-click "rule." This position was further solidified via FDA's 2014 guidance on space-limited contexts (the so-called "Twitter Guidance") that directly addressed the use of Twitter and search engine marketing formats that explicitly limit the number of characters. In that guidance, FDA asserted, "Regardless of character space constraints that may be present on certain Internet/social media platforms, if a firm chooses to make a product benefit claim, the firm should also incorporate risk information within the same character-space-limited communication." This is as explicit a rejection of any version of a one-click rule as FDA could possibly have made.

Just one sentence earlier in the guidance, FDA further asserted that, "If an accurate and balanced presentation of both risks and benefits of a specific product is not possible within the constraints of the platform, then the firm should reconsider using that platform for the intended promotional message (other than for permitted reminder promotion)."

Combined, these two statements established a framework that FDA was explicitly acknowledging could not be used by some manufacturers of prescription products for making claims about the benefits of their products. The consequences of this framework is that in certain contexts only products not subject to FDA's fair balance requirement would be able to provide benefit information about their products.

Of course, "benefit" information includes any suggestion of the product's indication. In practice, this means that prescription products manufacturers are frequently prevented from letting people know that their product(s) are possible treatment options for them; and that FDA's official position, as expressed in the 2014 guidance, is that this is fine.

Many people objected to this aspect of the draft guidance (see, for example, the comments from PhRMA), and that resulted in a brief movement to include a version of the one-click rule in the 21st Century Cures Act.

In that context, FDA's openness to studying these issues is a major step forward. Rather than simply assuming without any evidence that the public is harmed by companies following some version of a one-click rule, FDA is actually studying the issue.

This positive development is balanced, however, with the study design itself. In the proposed study, FDA is comparing a format that makes use of a one-click rule with a format that follows the recommendations from the 2014 guidance. One problem with this study design is that it is comparing a format that the FDA has acknowledged is not available to all product manufacturers because of the nature of their specific indications and risks. Indeed, I'm not aware of a single company that has attempted to use the format FDA demonstrated in that guidance for Google search or a Twitter ad.*

In addition, although FDA's willingness to study this topic is refreshing, the study announcement coming late in 2016 would seem to indicate that the status quo will remain for several years. It has been more than a year since FDA has released any new or updated guidance related to advertising and promotion (the last one was a minor revision in August of 2015), and the existing FDA guidance on space-constrained contexts has some glaring issues, independent of the position on one-click.

Taking a generous view of FDA's speed in fielding this research, it would be difficult to imagine that the final study results would be available before the end of 2017. FDA absolutely takes the work of its research team into account in developing guidance, including the ad-promo research. That probably means that the earliest we would see any update to the 2014 guidance would be 2018.

That's four years after FDA released the draft guidance and nine years after the 2009 hearings. FDA can't be expected to provide guidance that keeps up with the pace of technological change. Indeed, I think that's a virtue rather than a drawback to FDA's approach. It's better to have guidance that lags slightly behind innovation rather than wasting time developing guidance on topics that prove to be mere flashes in the pan. Consider the wasted effort if FDA had developed a guidance dedicated to Sidewiki after its 2009 hearings.

This, however, is a very different situation. FDA's enforcement activity related to its rejection of any version of the one-click rule has spanned nearly 20 years. Throughout that time, marketers of prescription products who want to inform the public about how they can help have been hindered in the ability to make that information available in the platforms that people are showing they prefer. And only now is FDA announcing its intention to see whether that position has any basis in actual experience.

* If anyone is aware of such an ad, please share it in the comments or via the contact form in the right rail.

The basic idea behind any version of the one-click rule is that companies can meet their fair balance requirement (21 CFR 202.1(e)(5)(ii)) by including a hyperlink to the risk information, rather than by providing the risk information itself in the original communication. As I've written about previously, this idea has had significant allure for marketers of prescription products but there has never been any indication from the FDA that it was open to it...until now.

I have been working with a few different clients preparing comments on the study proposal outlined by the FDA. Those will be posted to the docket and available for public view at a later date.

In this post, I wanted to take a step back and look at what this study means (and what it doesn't mean) for the immediate and future use of space-limited contexts by prescription product manufacturers and FDA guidance about this issue.

In 1998, FDA took its first enforcement action for Internet marketing. At the time, the FDA noted that "the link to the full prescribing information alone is insufficient to meet the requirements...that advertisements contain fair balance."

This began an 18-year history of the FDA making clear that it did not acknowledge a one-click "rule." This position was further solidified via FDA's 2014 guidance on space-limited contexts (the so-called "Twitter Guidance") that directly addressed the use of Twitter and search engine marketing formats that explicitly limit the number of characters. In that guidance, FDA asserted, "Regardless of character space constraints that may be present on certain Internet/social media platforms, if a firm chooses to make a product benefit claim, the firm should also incorporate risk information within the same character-space-limited communication." This is as explicit a rejection of any version of a one-click rule as FDA could possibly have made.

Just one sentence earlier in the guidance, FDA further asserted that, "If an accurate and balanced presentation of both risks and benefits of a specific product is not possible within the constraints of the platform, then the firm should reconsider using that platform for the intended promotional message (other than for permitted reminder promotion)."

Combined, these two statements established a framework that FDA was explicitly acknowledging could not be used by some manufacturers of prescription products for making claims about the benefits of their products. The consequences of this framework is that in certain contexts only products not subject to FDA's fair balance requirement would be able to provide benefit information about their products.

Of course, "benefit" information includes any suggestion of the product's indication. In practice, this means that prescription products manufacturers are frequently prevented from letting people know that their product(s) are possible treatment options for them; and that FDA's official position, as expressed in the 2014 guidance, is that this is fine.

Many people objected to this aspect of the draft guidance (see, for example, the comments from PhRMA), and that resulted in a brief movement to include a version of the one-click rule in the 21st Century Cures Act.

In that context, FDA's openness to studying these issues is a major step forward. Rather than simply assuming without any evidence that the public is harmed by companies following some version of a one-click rule, FDA is actually studying the issue.

This positive development is balanced, however, with the study design itself. In the proposed study, FDA is comparing a format that makes use of a one-click rule with a format that follows the recommendations from the 2014 guidance. One problem with this study design is that it is comparing a format that the FDA has acknowledged is not available to all product manufacturers because of the nature of their specific indications and risks. Indeed, I'm not aware of a single company that has attempted to use the format FDA demonstrated in that guidance for Google search or a Twitter ad.*

In addition, although FDA's willingness to study this topic is refreshing, the study announcement coming late in 2016 would seem to indicate that the status quo will remain for several years. It has been more than a year since FDA has released any new or updated guidance related to advertising and promotion (the last one was a minor revision in August of 2015), and the existing FDA guidance on space-constrained contexts has some glaring issues, independent of the position on one-click.

Taking a generous view of FDA's speed in fielding this research, it would be difficult to imagine that the final study results would be available before the end of 2017. FDA absolutely takes the work of its research team into account in developing guidance, including the ad-promo research. That probably means that the earliest we would see any update to the 2014 guidance would be 2018.

That's four years after FDA released the draft guidance and nine years after the 2009 hearings. FDA can't be expected to provide guidance that keeps up with the pace of technological change. Indeed, I think that's a virtue rather than a drawback to FDA's approach. It's better to have guidance that lags slightly behind innovation rather than wasting time developing guidance on topics that prove to be mere flashes in the pan. Consider the wasted effort if FDA had developed a guidance dedicated to Sidewiki after its 2009 hearings.

This, however, is a very different situation. FDA's enforcement activity related to its rejection of any version of the one-click rule has spanned nearly 20 years. Throughout that time, marketers of prescription products who want to inform the public about how they can help have been hindered in the ability to make that information available in the platforms that people are showing they prefer. And only now is FDA announcing its intention to see whether that position has any basis in actual experience.

* If anyone is aware of such an ad, please share it in the comments or via the contact form in the right rail.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)